Guest Blog: Rev Dave Talks Bob Dylan

Rev Dave part philosopher, part theologian and part singer-songwriter — he’s been baptized by the blues.

This blog is the first of a serialized engagement with the music of Bob Dylan. It will be collaboration between me and my old friend Rick Rennie (from Winnipeg by way of Little St. Lawrence). We will try to publish every two months.

I’m looking forward to this series as a chance to have a discussion with someone whose opinion I value and to share that with you. I hope you enjoy it too.

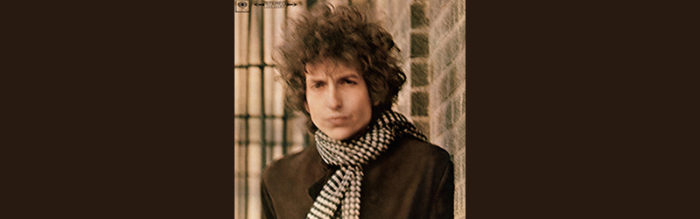

Dylan 1

The strangeness and alienation of 2020 were exacerbated by the fact that in March a 79-year-old Bob Dylan released a 17-minute song, “Murder Most Foul,” that reached number one on Billboard’s digital sales chart. We listened to the song and subsequent album Rough and Rowdy Ways in the social isolation with which we responded to Covid-19. It felt resonant with our time, with the loneliness and pervasive sense of loss that seem core aspects of our pandemic experience. Dylan has suggested that the murder of JFK marked the beginning of the age of the Anti-Christ. Perhaps we are experiencing something of the culmination of that figuratively haunting phrase in our current time.

Rick and I began to reflect together on the place of Rough and Rowdy Ways in Dylan’s extensive discography, and this brought us to questions of rank. We agreed with surprising ease that Blonde on Blonde deserves first place and decided that we’d like to think through his oeuvre using this fine double album as our touchstone.

All art worthy of the name is revelatory. Something unseen and unknown emerges in the dance of artist, medium, and audience, something unexpected shimmering silver like a salmon that you can catch but not hold in your hands, not without killing it, that is. Songs of this kind often contain streams of complexity and simplicity, which warrant listening and re-listening over time, and their great beauty is in the endless, even infinite, revelatory power they harness. Time and time again we have been struck by the newness and vitality that erupt when we return to Dylan’s work. “Murder Most Foul” brought this home. It reminded us of Faulkner’s oft-repeated saying, “The past is not dead, it is not even past.”

And so we return again to Blonde on Blonde; it has come to life for us anew reaching across 54 years to inspire and enlighten us, to hold us in its spell as we reflect and reconsider, as we pursue its layered serpentine course. It is worth considering here also that we the listeners are now many years on from having first encountered the songs in our youth. What emerges from the interplay among artist, work, and audience is constantly reshaped by the experiences of the listener, which is part of what gives art new powers of revelation.

We were struck almost immediately by the sense of play that wanders through the album. “Rainy Day Women No. 12 & 35,” with its jangling Salvation Army Band sensibility, and its off-kilter melody that weaves and totters but doesn’t fall, brings together both a jocular play on words between getting high and being killed by granite. If we focus on the surface play, we might miss the deadly seriousness of stoning, the implicit question about who has this authority and right of judgment. The song also, perhaps, expresses the moment of rebellion against authoritarian control in the simple resistance of getting high, posing the question of whether getting high is an adequate response to authoritarianism.

What is to be said about his more overtly religious albums in this light?[1] The sense of play at a structural level throughout Dylan’s writing is often exemplified in the relation of two elements, unity and fragmentation. It has proven worthwhile for us to ask about the songs, albums and their history, what are the fragments he observes and what are “the things that remain.”[2]

Think of Blonde on Blonde’s, “I Want You”:

The guilty undertaker sighs

The lonesome organ grinder cries

The silver saxophones say I should refuse you

The cracked bells and washed-out horns

Blow into my face with scorn, but it’s

Not that way, I wasn’t born to lose you

Undertaker, organ grinder, saxophones, bells, and horns are guilty, lonesome, silver, cracked, washed out, and scornful. And yet beyond these fragments there is something in desire, in what the speaker wants, that propels him.[3] And yet, there is not here a simple expression of individual willfulness. “Stuck Inside of Mobile”and “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” portray characters trapped and paralyzed between two worlds, neither of which may be desirable or available. In response the will must in some sense be quieted: “Should I leave them by your gate/Or sad eyed lady should I wait.” And in “Mobile,” even the desire to communicate is thwarted: “I would send a message to find out if she’s talked, but the post office has been stolen and the mailbox is locked.” Also, “Here I sit so patiently waiting to find out what price, you have to pay to get out of going through these things twice.” There is longing, there is paralysis, but there is no resolution. If we take the image of patience as reflecting addiction here, then even the decision to resolve one’s longing will only lead to further longing.

This shows the influence of Beat Poetry on Dylan’s writing, with its endeavor to decenter the significance of will and the very sense of self and self-creation. It also provides insight into the purposive difficulty in telling who, what and where the narrator is in some Dylan songs.

Dylan’s acts of decentering engage basic American ideals and call these values into question. The notion of self is given basic expression in the American focus on individual freedom and right. In doing so, he challenges the notion that the pursuit of happiness can come to any final result, especially through the satisfaction of any one desire or set of desires.

So, Dylan portrays individuals with their current sets of beliefs and desires as swimming in a sea of systemic complexity and asks us to look at our selves in historical, social, religious, economic, political and other contexts. What we tend to believe about ourselves in the context of what we wish to achieve, our goals and desires, as well our practical everyday horizon are revealed as mere surface. Our desires are shaped by a multitude of forces — the media, pop culture, history, education. So, when Dylan sings (in “Mobile”), “Shakespeare he’s in the alley with his pointed shoes and his bells,” it may well be Shakespeare himself, whose historical reality extends into the present in his capacity still to reveal contemporary linguistic and imaginative possibilities. In his influence upon us, Shakespeare is not dead, he is not even past.

Dylan’s sense of time — with its complex amalgam of history, fate, chance, and destiny — is another trope through which he challenges the capacity of the will to exert itself upon and shape the world to its longing. In “Pledging my Time,” there is a sense of the need for a commitment but also of forces at play that are beyond the individual’s will:

Well, they sent for the ambulance

And one was sent.

Somebody got lucky

But it was an accident.

Now I’m pledging my time to you,

Hopin’ you’ll come through, too

The strength of the pledge does not constrain the power of accident and temporality. The commitment of “Pledging my Time”is subject to an otherness that the individual cannot shape, as expressed in “Just Like a Woman”:

It was raining from the first

And I was dying there of thirst

So I came in here

And your long-time curse hurts

But what’s worse

Is this pain in here

I can’t stay in here

Ain’t it clear that—

I just can’t fit.

But recourse beyond temporality and otherness is likewise no easy answer. In “Visions of Johana,” “Inside the museums, Infinity goes up on trial/ Voices echo this is what salvation must be like after a while.” Even if the struggle of will with time and destiny could be resolved, and desires fulfilled, this would bring no ultimate satisfaction. As our narrator cautions on a later album, There’s only one step down from here baby/It’s called the land of permanent bliss. Dylan is not looking to overcome complexity but to embrace it.

We’ve had fun talking with each other about Blonde on Blonde; this is the most Rick and I have hung out in years, albeit at a distance. And, of course, we’ve barely dipped into this deep well of an album. We haven’t even mentioned, for example, the commentary on capitalist materialism inherent in songs like “Leopard Skin Pill Box Hat”: “You know it balances on your head just like a mattress balances on a bottle of wine.”

We should be back with a go at another Dylan album in January.

[1] Slow Train Coming, 1979, Saved, 1980, Shot of Love, 1981.

[2] When You Gonna Wake Up, Slow Train Coming, 1979.

[3] Something in this verse reminds me of the process of bringing together lyrics and music in songwriting, there may even be an allusion to the song Born to Lose. There are both simple metaphors and metaphorical structures at play.